They Brought Their Songs with Them:

Songs from the Dust Bowl

The songs in the Library of Congress collection, Voices from the Dust Bowl, showcase the cultural influences brought to California in the 1930s by refugees from the twin economic and ecological disasters of the Great Depression and the droughts that created the Dust Bowl. Displaced from their land, more than 300,000 people made the long and difficult trek to California to find work. They came not only from Oklahoma, where the drought had been most severe, but from Texas, Arkansas, Missouri, Nebraska, Kansas, New Mexico and Arizona; and they brought with them their songs, their dances, and their cultural heritage.

California was by no means the Promised Land for the migrants. Although the weather was better, and the agricultural season longer and more varied, the Depression had hit California as well. Wages for California farm workers had never been high, but during the Depression they plummeted, in some cases to less than a quarter of pre-1929 levels, and the arrival of the Dust Bowl refugees depressed wages even more. Families were unable to support themselves even with all their members working in the fields, and were reduced to living in roadside squatters’ camps or “ditchbank camps” next to farmers’ irrigation ditches.

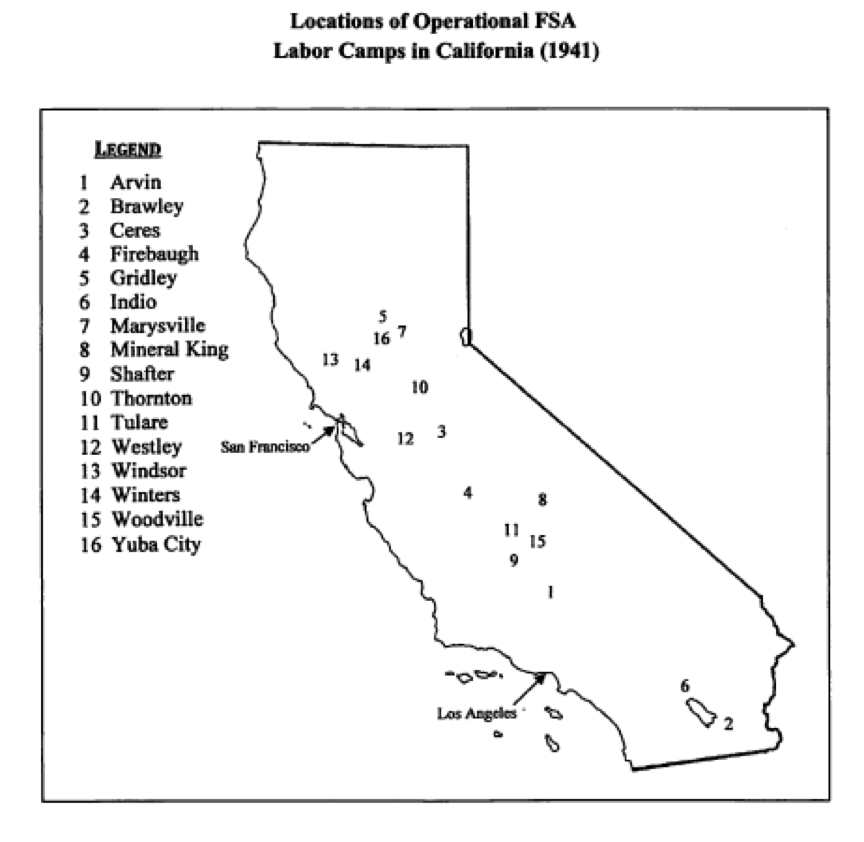

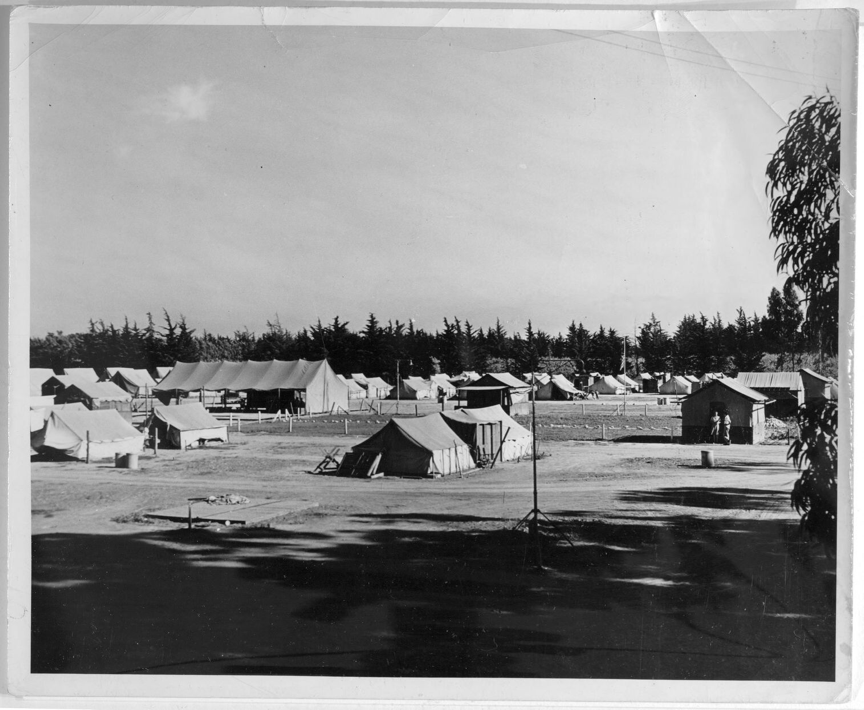

The Farm Security Administration, a New Deal agency founded in 1937 to combat rural poverty, responded to this desperate situation by building a series of camps for migratory workers. The first of these camps was the Arvin Migratory Labor Camp, established by the FSA in the cotton-growing region of the San Joaquin Valley, and notable as the setting of John Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes of Wrath. It provided clean campsites, hot water, sanitary facilities and medical care for a small rental fee. Later, the campsites, which often flooded in the rainy season, were improved by building tent platforms, and by 1939 more permanent housing had been added, as well as space for vegetable gardens. Community centers provided libraries, schools for the children, and a space for social activities. The camps were set up to provide a model of participatory democracy, and educational programs developed to assist the migrants’ entry into California society. By 1941, there were 16 such camps in California.

Despite the improvement in their living situations, there were still many factors causing conflicts among the workers at the camps. Living in close quarters with people of different backgrounds caused social strains. There were divisions based on religion, class, and politics. Labor strikes drew lines between strikers and strikebreakers.

But in music, the migrants found a source of shared values and community. Music provided a link to home for homeless people. It brought people together in difficult conditions. People from many places shared their songs and dances, and the musical styles that came from this sharing became a force in the development of country and popular music and contributed a new cultural element to California’s agricultural regions. As one informant remarked, “If it weren’t for Texas, Oklahoma and Arkansas, there wouldn’t be much of California, would there?”

Among the people who came to the FSA camps to document their culture were Charles L. Todd and Robert Sonkin. Supported by the Archive of American Folk Song of the Library of Congress, they visited many of the camps in 1940 and 1941 and recorded songs, instrumental music, interviews, and meetings of the governing councils of the camps. A selection of their recordings, photographs, field notes and other documentation, as well as informative articles and teaching resources, is available in the Library of Congress American Folklife Center’s online presentation Voices from the Dust Bowl: The Charles L. Todd and Robert Sonkin Migrant Worker Collection.

A variety of musical sources and genres are represented by the songs sung in the FSA camps. The following songs can be found in the American Folk Song Collection, with text and musical transcriptions and background information.

The oldest songs sung in the camps come from the Anglo-Celtic ballad tradition, carried to the Americas by successive waves of immigrants from the British Isles.

Barbara Allen (Child Ballad 84) is one of the most popular and widespread English ballads in the United States, dating from at least the 17th century.

Lloyd Bateman is an American version of the English ballad Lord Bateman or Young Beichan (Child Ballad 53). The ballad was first printed in 1624, but is so widespread in so many countries as to point to an origin in the time of the Crusades. Much of the text of this singer’s performance is remarkably similar to 17th and 18th century versions, demonstrating how the repetitive and rhetorical forms of the ballad assist the process of oral transmission.

Ballads of American origin are represented here by Jesse James, perhaps the most famous example of the outlaw ballad tradition. This song, which spread rapidly following the 1882 death of the notorious Confederate guerrilla turned bank robber, made a folk hero out of a man who carried out the “Civil War by other means” in a decades-long career of brutality and crime.

In quite another vein, the Dust Bowl refugees brought to California the tradition of the play-party. Dancing was considered sinful by a large swath of the population of the South and the Midwest, but “dancing” was defined as movement accompanied by instruments, particularly the fiddle, considered the “devil’s instrument.” But dances accompanied only by the singing of the participants were free from this proscription. Thus the “play-party” arose and spread to many states, from which it travelled to California in the migrants’ cultural baggage. The Todd-Sonkin collection contains rare examples of actual recordings of play-parties being danced and sung in the community centers of the FSA camps.

Examples in this collection include Skip to My Lou, Sent My Brown Jug Downtown, and Miller Boy, all of which also include detailed dance directions.

Children’s songs are represented by Chimchack, a rare variant of the widespread cumulative song “Bought Me a Cat,” which has charmed generations of youngsters with its combination of the humorous depictions of animal sounds and the delight of the increasing demand of remembering the cumulative list of creatures so depicted.

In the same humorous vein is Soldier, Won’t You Marry Me, an extended musical joke, probably of fairly recent origin (late 18th century), and popular on both sides of the Atlantic, though most likely of English origin.

The long shadow of the African-American spiritual and its widespread influence on Anglo-American popular music can be seen in a simple, stripped-down version of She’ll Be Coming Around the Mountain, the secular descendant of the slave-era spiritual “When the Chariot Comes,” with its startling echoes of both the Second Coming of Christ and the hope and force of the Underground Railroad.

The bluegrass song Charming Betsy brings us closer to the world of country music, with its gently subversive assertion of human equality, surely appreciated in the migrant camps:

Rich man, he lives in a big brick house,

Poor man, he do’s the same;

I live way down in the county jail—

It’s a brick house, just the same.

The new world of the migrants also rears its head in songs like Railroader, acknowledging the triumph of the post-pastoral world with sentiments such as:

I would not marry a farmer, he’s always in the dirt;

I’d rather marry an engineer who wears a striped shirt.

The emotional world of the migrants finds its most poignant expression in I’m Goin’ Down the Road Feelin’ Bad “, a white blues of universal appeal and uncertain origin” (Ralph Rinzler) which has been sung by Woody Guthrie and the Grateful Dead as well as by the unsung migrants who had experienced first-hand those universal aspects of the American experience expressed by, on the one hand, the self-assertion of “I ain’t gonna be treated this-a-way” and the extraordinary vision of “I’m going where the climate suits my clothes.”

What it takes to realize that vision is hinted at in the songs of union organizers, represented here by Fight for Union Recognition, sung to the tune of “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad.” This song, created during the cotton workers’ strike of 1939, reminds us of all the moments in history when a people’s movement called for new words set to old tunes: from Martin Luther’s repurposing of troubadour songs, to the re-visioning of spirituals in the Civil Rights movement.

We think of cotton pickers in terms of the South and the legacy of slavery, but California has long been a major cotton-producing state. The “Eighty cents won’t even feed us” in this song refers to the wages being offered by the cotton farmers: eighty cents for a hundred pounds of cotton. A strong grown man could pick a maximum of 200-300 pounds a day; most workers could pick considerably less, for a wage of perhaps twelve cents per hour. This song reminds us that the struggle for justice for agricultural workers has been decades in the making, and continues to this day.

The lives of the migrant workers in the FSA camps would not substantially improve until later into World War II, when California wartime industries began to provide steady work and higher wages, allowing the Dust Bowl migrants to enter fully into California society, where their descendants live today. And the efforts to improve the lives of agricultural workers had to wait until the 1960s, and the work of Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers.

The FSA camps, and the role of this Federal agency in the lives of so many people, is little known today. But the legacy of the FSA continues to influence our culture through the project for which it is perhaps best known today: the photographic project of documenting the lives of the rural poor, which became a major influence in how people perceived the Depression. Hundreds of thousands of photographs were created by such noted photographers as Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans and Gordon Parks. The 164,000 images that have survived have been published online by the Library of Congress.